On the plus side, we now have a serious climate bill in Congress. On the downside, it suffers from the problem that the EU, and indeed all governments have when dealing with a social problem: laws do not work. Making any desired activity illegal generates a black market, encourages corruption and inevitably results in selective enforcement that targets the politically weak. When you add to the mix a problem as complicated as climate change, setting emissions targets, temperature targets or even sea level targets is foolhardy. We have fairly good estimates for what amounts of carbon dioxide will cause different levels of calamity, but we don't have a good system of forcing anyone to stay within their limits.

Actually, we do, but we'd like to avoid FDR-style stimulus if possible. Cap and trade promises to be as much of a boondoggle as the CAFE standards. Essentially, they were an attempt to drive production of fuel efficient vehicles without bothering to stimulate demand for them. Cap and trade without very strong enforcement and carbon costs that track inflation will have the same effect.

How about an alternative: a carbon tax. Sure, don't call it that, but a slowly phased-in tax that guarantees certain sources of energy will lose economic value over time will drive efficiency and alternative source investments. So, as a start, I'm a big fan of the "Gush-Up" idea funded by a slowly increasing gasoline tax at the slow but steady rate of $.05/yr. Here's how it could work:

Assume gasoline sales will be at least 90% what they were last year. That allows $5.9billion to be spent on the program this year. Lop off another 5% for program administration, and you have $5.6billion for a "bottom up" car company stimulus this year.

The $5.6billion would then go to boost the trade in value of old, heavy cars. I recommend a formula along these lines:

Boost = (Gross Vehicle Weight)*(Age-10)

As the program gets advertising (part of the administration budget), there will hopefully be a surge of people coming in to buy cars. While the tax is regressive, it will have a much larger benefit for poor communities that have been keeping old, polluting cars around because they could not afford to replace them. It should also ease the strain on infrastructure as lighter vehicles replace heavier ones. The fact that it would not provide enough funds for everyone to trade in their vehicles right away would help smooth demand from year to year.

Thus, with gas prices going up steadily, the owners of old gas guzzlers will have an incentive to go buy an updated vehicle. To the extent they can get credit or cover the remaining cost of a new car, it benefits the auto manufactures directly. Otherwise, it raises the price of newer trade ins, allowing people who want to trade in their older Honda Accord on a new Chevy Malibu to do so more easily. Given the heavy US government investment in GM and Chrysler, it makes sense to arrange the "pilot" program to favor their dealerships.

Devoted to the study of sustainable, universal pie making.

Tuesday, March 31, 2009

Thursday, March 26, 2009

Making Aid Work, in a Pie Friendly Way

The second in the series of summaries and commentaries on the essays in Reinventing Foreign Aid

The problem with aid, according to Easterly and seconded by Banerjee and He, is that the planners, funders and managers of aid programs are not accountable to the recipients. This leads to the classic problem of socialism, persistent misalocation of resources. Addressing this in a way that does not involve simply giving money to poor people requires a mechanism to create transparent accountability.

Banerjee and He propose treating aid interventions as medications, and subject them to randomized trials. Historically, this data-driven approach has encountered 4 major objections:

(1) Research is an expense that reduces the efficiency of aid giving

(2) Conducting these studies is very slow and so hinders the roll-out of new aid programs.

(3) There are so few projects for which there are randomized clinical trials we would not be able spend the current aid budget on them. This could result in smaller aid budgets, since funds would move to other priorities.

(4) Adopting this will limit projects to ones that have easily measured objectives.

Banerjee and He have clear responses to the first three, and I think we start seeing role of PMCIN in #4.

Response to #1:

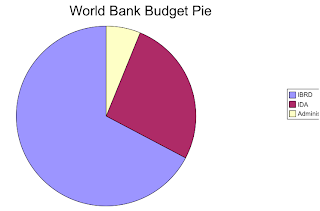

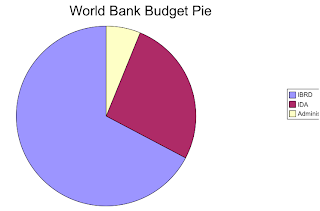

If efficiency in terms of (money to recipients)/(money donated) is the primary goal, then we should give people money directly. The World Bank spent an average of $1.4billion per year administering the $21.6billion in loans it made between 1994 and 2001. This does not include the cost of administering large projects within the recipient country, both legitimate and due to corruption.

Response to #2: Milton Friedman makes a blistering critique of the Food and Drug Administration's approach of "no sales until proven safe" for new drugs for this same reason, preferring instead an to put risk decisions in the hands of affected individuals. Waiting for long and complex trials of life-saving drugs to approve their use for terminally ill patients leads to more deaths if the drugs work as expected, and if not the terminally ill would not be all that adversely affected. Development aid, however, is different, since the "patient" is not an individual who is choosing between bad and worse, but a community with little power over the type of aid offered. Therefore, spending two or three years testing pilot aid programs rigorously is a small "loss" compared to the years wasted on improper programs that are rolled out quickly.

World Bank and Asia Development Bank are the only large aid organizations that publish data on the performance of their programs. In general, the share of a project funding by the World Bank increases slightly if its performance, as measured by the WB, improves. On the other hand, programs that were initially having doing well were generally less well funded by the WB. The ADB's funding model seems to reward failure, as higher funding generally indicates poor initial and changing outcomes. In other words, the larger the portion of the project's pie from one of these agencies, the smaller that pie is likely to be. Of course, the measure of pie size itself depends on the banks.

Response to #3: It's hard to imagine a statement that better expresses the perversity of the incentives in the aid community. It happens because the easiest measure of work done is money spent. How well or efficiently that money is spent gets into a separate and longish debate over the meaning of those terms, which is what we are discussing now.

In terms of aid today, very few projects have a rigorous study of their effectiveness, leading to an impression that few programs can handle rigorous study. While the slice of the aid pie devoted to clinically tested programs is pretty small, if these programs were scaled up worldwide they could consume most of the existing aid budget. The remainder, according to Banerjee and He, could be used to provide direct food subsidies, a suboptimal but occasionally necessary approach. I would argue instead for development of non-governmental relief capacity, since disasters cannot be budgeted in advance and capacity requires maintenance, for both equipment and recurrent training of personnel.

Response to #4: The authors do not suggest a concrete solution to the objection that imposing an ethos of rigorous testing on aid programs will lead to a "teach to the test" mentality in the aid community. The comparable debate in education, however, is instructive. The paradigm must change from one in which descions are made based on human intuition to one in which an impersonal process determines who is "right."

A more positive statement of this approach is that it moves the debate about aid away from "which programs do we like most?" to "what outcomes do we want to seek?" Different organizations will probably adopt different standards to judge their effectiveness, and it will be up to donors to decide what level of objectivity and risk they want to fund. This is a far better situation than the conditions laid out in the US's Millenium Challenge Account, which requires governance and market reforms in the recipient country that are beyond the means of the poorest nations on Earth.

Simply knowing that an evaluation is coming tends to improve performance, c.f. kids who brush their teeth extra hard before a trip to the dentist. Supporting this new paradigm is going to require a widely accepted, unambiguous measure of prosperity that is relevant around the world. Further, the application of this test should be funded entirely separately from the aid program, preferably by an organization with no more overhead than a rolling pin and a deep dish pie plate. I think I'm gong to start a travel blog.

The problem with aid, according to Easterly and seconded by Banerjee and He, is that the planners, funders and managers of aid programs are not accountable to the recipients. This leads to the classic problem of socialism, persistent misalocation of resources. Addressing this in a way that does not involve simply giving money to poor people requires a mechanism to create transparent accountability.

Banerjee and He propose treating aid interventions as medications, and subject them to randomized trials. Historically, this data-driven approach has encountered 4 major objections:

(1) Research is an expense that reduces the efficiency of aid giving

(2) Conducting these studies is very slow and so hinders the roll-out of new aid programs.

(3) There are so few projects for which there are randomized clinical trials we would not be able spend the current aid budget on them. This could result in smaller aid budgets, since funds would move to other priorities.

(4) Adopting this will limit projects to ones that have easily measured objectives.

Banerjee and He have clear responses to the first three, and I think we start seeing role of PMCIN in #4.

Response to #1:

If efficiency in terms of (money to recipients)/(money donated) is the primary goal, then we should give people money directly. The World Bank spent an average of $1.4billion per year administering the $21.6billion in loans it made between 1994 and 2001. This does not include the cost of administering large projects within the recipient country, both legitimate and due to corruption.

Response to #2: Milton Friedman makes a blistering critique of the Food and Drug Administration's approach of "no sales until proven safe" for new drugs for this same reason, preferring instead an to put risk decisions in the hands of affected individuals. Waiting for long and complex trials of life-saving drugs to approve their use for terminally ill patients leads to more deaths if the drugs work as expected, and if not the terminally ill would not be all that adversely affected. Development aid, however, is different, since the "patient" is not an individual who is choosing between bad and worse, but a community with little power over the type of aid offered. Therefore, spending two or three years testing pilot aid programs rigorously is a small "loss" compared to the years wasted on improper programs that are rolled out quickly.

World Bank and Asia Development Bank are the only large aid organizations that publish data on the performance of their programs. In general, the share of a project funding by the World Bank increases slightly if its performance, as measured by the WB, improves. On the other hand, programs that were initially having doing well were generally less well funded by the WB. The ADB's funding model seems to reward failure, as higher funding generally indicates poor initial and changing outcomes. In other words, the larger the portion of the project's pie from one of these agencies, the smaller that pie is likely to be. Of course, the measure of pie size itself depends on the banks.

Response to #3: It's hard to imagine a statement that better expresses the perversity of the incentives in the aid community. It happens because the easiest measure of work done is money spent. How well or efficiently that money is spent gets into a separate and longish debate over the meaning of those terms, which is what we are discussing now.

In terms of aid today, very few projects have a rigorous study of their effectiveness, leading to an impression that few programs can handle rigorous study. While the slice of the aid pie devoted to clinically tested programs is pretty small, if these programs were scaled up worldwide they could consume most of the existing aid budget. The remainder, according to Banerjee and He, could be used to provide direct food subsidies, a suboptimal but occasionally necessary approach. I would argue instead for development of non-governmental relief capacity, since disasters cannot be budgeted in advance and capacity requires maintenance, for both equipment and recurrent training of personnel.

Response to #4: The authors do not suggest a concrete solution to the objection that imposing an ethos of rigorous testing on aid programs will lead to a "teach to the test" mentality in the aid community. The comparable debate in education, however, is instructive. The paradigm must change from one in which descions are made based on human intuition to one in which an impersonal process determines who is "right."

A more positive statement of this approach is that it moves the debate about aid away from "which programs do we like most?" to "what outcomes do we want to seek?" Different organizations will probably adopt different standards to judge their effectiveness, and it will be up to donors to decide what level of objectivity and risk they want to fund. This is a far better situation than the conditions laid out in the US's Millenium Challenge Account, which requires governance and market reforms in the recipient country that are beyond the means of the poorest nations on Earth.

Simply knowing that an evaluation is coming tends to improve performance, c.f. kids who brush their teeth extra hard before a trip to the dentist. Supporting this new paradigm is going to require a widely accepted, unambiguous measure of prosperity that is relevant around the world. Further, the application of this test should be funded entirely separately from the aid program, preferably by an organization with no more overhead than a rolling pin and a deep dish pie plate. I think I'm gong to start a travel blog.

Sunday, March 22, 2009

Prosperity and legitimacy

There are, in general, three three things a government needs to create and sustain legitimacy:

(1) National Identity: The government embodies the ideals and interests of a self-defining "people" (cultural/racial/ethnic/religious/etc) .

(2) Law and Order: The government has the monopoly on overwhelming violence, and no one is inclined to challenge it.

(3) Prosperity: Life is better with the government than without it.

The US is pretty comfortable with (1) and (2). The ongoing debate about what it means to be "American" will likely, hopefully, never end. Our political leaders are drawn not from any particular demographic; waves of immigrants have contributed. Our inclusive political and commercial process is more appealing than trying to seize power outside of them. Our military and law enforcement systems are not perfect, but it's tough to find better.

However, the third leg of the stool is the tricky one. Prosperity is a highly subjective thing, but in general the greater the ability of a society to allow individuals to consume resources, the more prosperous it is. This is why, in a society that simply has too much debt, the stated policy goal is to "restore lending." To do otherwise is to admit that we've run out of future to raid, and our government has failed to provide the prosperity we expect. As always, it is the new middle class that reacts most strongly to losing its run on the ladder, but try to imagine an American city losing reliable internet, phone, electricity and water services.

So, why bail out AIG? Because, if you go back to my little story of Bob's Investment House, the reason WSB was willing to give BIH that big loan was the insurance policy AIG was willing to write against BIH defaulting. The "guaranteed 5%" investment BIH found was backed up by a second AIG insurance policy. So, if anyone seriously believed that AIG would collapse, WSB would "call" its loan to BIH (much like when you pull money out of a savings account), BIH's clients would demand their money back, and the value of all the mortgages in the MBS would collapse as Bob and his staff tried to arrange a firesale while everyone else was doing the same thing. The knock on effect is that an unpleasant deleveraging spiral like we're seeing now would turn into a pretty massive calamity as the banks that hold the cash for large corporations fail, leaving even well-heeled companies unable to pay their workers. City services would fail as those workers weren't able to pay their taxes, and huge swathes of the country soon start to resemble third world countries with inadequate power and sanitation.

The problem is not the bailouts and certainly not the bonuses. From policy makers to investors to voters, we all made mistakes, and now we're trying to clean up the mess. The bigger issue here is whether or not we want a world in which "prosperity" means committing as many people as possible to give as much of their future income as possible to securities owners (like hedge and pension funds) and financial services companies. Some good things to get upset about are that our entire system is based on unsustainable borrowing against future income, that we need unsustainable resource harvesting and consumption, and that the path to "prosperity" offered today was a path to slavery in the past.

(1) National Identity: The government embodies the ideals and interests of a self-defining "people" (cultural/racial/ethnic/religious/etc) .

(2) Law and Order: The government has the monopoly on overwhelming violence, and no one is inclined to challenge it.

(3) Prosperity: Life is better with the government than without it.

The US is pretty comfortable with (1) and (2). The ongoing debate about what it means to be "American" will likely, hopefully, never end. Our political leaders are drawn not from any particular demographic; waves of immigrants have contributed. Our inclusive political and commercial process is more appealing than trying to seize power outside of them. Our military and law enforcement systems are not perfect, but it's tough to find better.

However, the third leg of the stool is the tricky one. Prosperity is a highly subjective thing, but in general the greater the ability of a society to allow individuals to consume resources, the more prosperous it is. This is why, in a society that simply has too much debt, the stated policy goal is to "restore lending." To do otherwise is to admit that we've run out of future to raid, and our government has failed to provide the prosperity we expect. As always, it is the new middle class that reacts most strongly to losing its run on the ladder, but try to imagine an American city losing reliable internet, phone, electricity and water services.

So, why bail out AIG? Because, if you go back to my little story of Bob's Investment House, the reason WSB was willing to give BIH that big loan was the insurance policy AIG was willing to write against BIH defaulting. The "guaranteed 5%" investment BIH found was backed up by a second AIG insurance policy. So, if anyone seriously believed that AIG would collapse, WSB would "call" its loan to BIH (much like when you pull money out of a savings account), BIH's clients would demand their money back, and the value of all the mortgages in the MBS would collapse as Bob and his staff tried to arrange a firesale while everyone else was doing the same thing. The knock on effect is that an unpleasant deleveraging spiral like we're seeing now would turn into a pretty massive calamity as the banks that hold the cash for large corporations fail, leaving even well-heeled companies unable to pay their workers. City services would fail as those workers weren't able to pay their taxes, and huge swathes of the country soon start to resemble third world countries with inadequate power and sanitation.

The problem is not the bailouts and certainly not the bonuses. From policy makers to investors to voters, we all made mistakes, and now we're trying to clean up the mess. The bigger issue here is whether or not we want a world in which "prosperity" means committing as many people as possible to give as much of their future income as possible to securities owners (like hedge and pension funds) and financial services companies. Some good things to get upset about are that our entire system is based on unsustainable borrowing against future income, that we need unsustainable resource harvesting and consumption, and that the path to "prosperity" offered today was a path to slavery in the past.

Thursday, March 19, 2009

An object lesson from AIG, cheap at the price

Many people reading the bit about sustainable, universal pie making as a policy objective tend to think that I'm closer to Marx than Hayek in my thinking. After all, the whole point of the pie-a-week notion of prosperity is that it is not resource intensive, and, in theory, could be achieved by a planned economy. History suggests otherwise. If you don't believe me, I'll spot you a rolling pin and a pie plate for a little trip North Korea, Cuba, Belarus or even Venezuela.

The problem, at least one among many, is that in a planned economy compensation is determined by political rather than economic forces. The way we determine the number of doctors, lawyers, ditch diggers, engineers, etc. in most of the world now is increase their pay when we need more and decrease it when we need fewer. In some cases, this system can get out balance, especially when governments try absorb risk. We, however, have a built-in correction mechanism that, while painful (or funny), sure beats the alternative.

So, at the low, low price of $160million (plus probably twice that in gov't employee and media air time), we get an object lesson in how a nationalized economy must respond to popular pressure. The result of this is going to be a flight of the people who best understand the financial WMD to smaller firms where, hopefully, they will be able to do less damage. The crisis will drag out an extra half year or more as the people willing to accept lower pay and the political risk of working Citi, AIG and others get up to speed on exactly what was going on, and despite all the calls for more lending, we won't see much.

The problem, at least one among many, is that in a planned economy compensation is determined by political rather than economic forces. The way we determine the number of doctors, lawyers, ditch diggers, engineers, etc. in most of the world now is increase their pay when we need more and decrease it when we need fewer. In some cases, this system can get out balance, especially when governments try absorb risk. We, however, have a built-in correction mechanism that, while painful (or funny), sure beats the alternative.

So, at the low, low price of $160million (plus probably twice that in gov't employee and media air time), we get an object lesson in how a nationalized economy must respond to popular pressure. The result of this is going to be a flight of the people who best understand the financial WMD to smaller firms where, hopefully, they will be able to do less damage. The crisis will drag out an extra half year or more as the people willing to accept lower pay and the political risk of working Citi, AIG and others get up to speed on exactly what was going on, and despite all the calls for more lending, we won't see much.

Tuesday, March 17, 2009

A higher pie-centric calling

William Easterly, the first person I've encountered in the foreign aid community to quote Hayek, edited a fantastic book book. The Introduction, written by Dr. Easterly, suggests that the foreign aid system is broken. Its original intention was, and it is sold today as, a means of giving people a boost out of the "poverty trap". Complicated plans have been developed, the most ambitious being the Millenium Development Goals. Each component in these plans builds on the others, creating a sort of chain used to pull the recipient out of poverty and into prosperity with one big heave. Unfortunately, the chain always seems to break before the trapped people can be pulled free.

Since each link in the chain is necessary, resources must be allocated to strengthen weak ones instead of reinforcing the strong ones. The will to pull is sustained by public personalities who remind us of our obligation to help those in need. And so the aid system sustains itself with the belief that a good plan will someday bear fruit. If only that darn chain wouldn't break and we could convince the pullers to just pull harder, we'd make it.

Dr. Easterly argues for a different model. Rather than thinking of planned aid as the key to ending poverty, think of it as providing a small boost. In other words, instead of a "poverty trap" with steep walls that must be cleared in one go, think of progress as a continuum. It isn't necessary, or even desirable, to try and plan a path to prosperity. Instead, foreign aid should be seen as a collection of ropes, each pulled independently with the modest goal of improving local conditions. The most effective "ropes" can be strengthened, while ones that don't yield results can be cast aside without endangering the whole system.

This approach, however, begs the question of what interventions are most effective. The bulk of the book is devoted to answering that question, and is by no means the final authority on the subject. I wonder if there's room in the debate for pie-based metrics . . .

Since each link in the chain is necessary, resources must be allocated to strengthen weak ones instead of reinforcing the strong ones. The will to pull is sustained by public personalities who remind us of our obligation to help those in need. And so the aid system sustains itself with the belief that a good plan will someday bear fruit. If only that darn chain wouldn't break and we could convince the pullers to just pull harder, we'd make it.

Dr. Easterly argues for a different model. Rather than thinking of planned aid as the key to ending poverty, think of it as providing a small boost. In other words, instead of a "poverty trap" with steep walls that must be cleared in one go, think of progress as a continuum. It isn't necessary, or even desirable, to try and plan a path to prosperity. Instead, foreign aid should be seen as a collection of ropes, each pulled independently with the modest goal of improving local conditions. The most effective "ropes" can be strengthened, while ones that don't yield results can be cast aside without endangering the whole system.

This approach, however, begs the question of what interventions are most effective. The bulk of the book is devoted to answering that question, and is by no means the final authority on the subject. I wonder if there's room in the debate for pie-based metrics . . .

Saturday, March 7, 2009

And back to econometrics

Back in September of last year, I proposed an economic index with the playful title of Pie Making Capacity in Nation, with the acronym "PMCIN", pronounced "pumpkin". I laid out some suggestions early on about how to compute it, but never went any farther. Now to see if I can implement those, and give us a more objective measure of how "pie friendly" various policies are.

Rather than try to do it all at once, I think I'll take a lesson from my own craft and work in stages. First, the "crust": the basic necessity of food. The fundamental question of pie making capacity is this: is enough food grown, harvested and available for everyone to meet basic needs and have enough left for a pie each week?

A good source of such data is the USDA website. They issue a regular World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates (WASDE) that breaks down production of various types of food. From this, it's pretty easy to subtract a healthy diet for a standard population, and then divide up the remainder by the amounts needed for pie making. Once I'm in the "wait for video processing" stage of my dissertation, I will try to write the script that collects that information and put it up on the blog as a widget. People willing to volunteer IT help will be rewarded.

Rather than try to do it all at once, I think I'll take a lesson from my own craft and work in stages. First, the "crust": the basic necessity of food. The fundamental question of pie making capacity is this: is enough food grown, harvested and available for everyone to meet basic needs and have enough left for a pie each week?

A good source of such data is the USDA website. They issue a regular World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates (WASDE) that breaks down production of various types of food. From this, it's pretty easy to subtract a healthy diet for a standard population, and then divide up the remainder by the amounts needed for pie making. Once I'm in the "wait for video processing" stage of my dissertation, I will try to write the script that collects that information and put it up on the blog as a widget. People willing to volunteer IT help will be rewarded.

Thursday, March 5, 2009

Discovery or NSF should hire this guy

We scientists are an exciting bunch, and I know just who the NSF or Discovery (or MTV) should hire to make that case: The McMurdo Station Jello Wrestling organizer. He's out of work, the economy's down, and it's time for science to be cool in the US.

I think he goes by Chef Bobby, at least that the guy credited with organizing the event pictured here [caution: visible underwear]. Science can be pretty dry and boring. Scientists don't have that problem. Let's let everyone know we can save the world and throw its best parties.

I think he goes by Chef Bobby, at least that the guy credited with organizing the event pictured here [caution: visible underwear]. Science can be pretty dry and boring. Scientists don't have that problem. Let's let everyone know we can save the world and throw its best parties.

Wednesday, March 4, 2009

Rational solutions are for rational problems

Psychology and behavioral economics suggest that people cling to hopes as hard as possible until they are completely dashed. Thus, when people are presented with an option of taking a small loss to avoid a big potential calamity or preserving the status quo, they almost always choose the latter. Hope is not a rational thing, and so getting people to move from what makes them feel good to what is actually good for them requires far more than rational arguments. Appeals must be made to humor, fear and hope in something else to be successful. Above all, the proponent of any change must offer a compelling narrative.

I learned this when a friend of mine, we'll call her "D", was dealing with a nasty break up as an undergrad. She'd fallen hard for a guy who had a second girlfriend an hour's drive away, and decided to drop her in favor of the more distant girl. D was quite upset, and her friends, including me, tried to console her with very convincing arguements that ex-bf was an asshole, liar, scoundrel and complete waste of food (in point of fact, he's not a bad guy and we get along fairly well today). Two weeks later we had made no progress, so I tried a different approach: "D, he eats nothing but potatoes and fried chicken, and you are what you eat. Look at his skin, kinda splotchy like an old spud. His nose, and jowls . . . Well, you can love an asshole. You can love a lying, cheating jerk. But D, can you love a chicken?" I wore a bright yellow shirt and did a little chicken dance to drive home the point. When she stopped laughing a couple hours later, she felt a little better. It would take time and new opportunities for her to move on completely, but giving up trying to be rational about the process helped all of us.

This is relevant to the two big discussions on this blog, the financial mess and sustainability. The problem with the the banks today is one of confidence. After realizing that too few debts would be repaid for the debt-fueled system we've had since the 1980s to continue working, businesses and consumers have started hoarding. Fixing it will involve convincing everyone involved to take their losses and move on, while restoring confidence in the surviving institutions. Most importantly, these include the regulatory bodies that were established during the Great Depression and have the power to seize and wind down insolvent institutions. By allowing zombie banks to survive, they undermine their own real resource: credibility. If the coming "stress tests" don't reveal substantial problems in two or more of the top twenty banks, no one will believe them. If no one believes that BofA or Citi are more than politically connected, hollow shells, then their counterparties' will be suspect, and the banking system will remain paralyzed. I think FDR's "bank holiday" did more to help ease the GD than his spending programs, since the banks that reopened had more support and investment could begin anew. Until everyone involved trusts bank balance sheets and regulators' authority, the market will be paralyzed by fear.

The other issue is sustainability. As Tim noted in the comments on the previous post, talk about changing life styles to benefit grandkids doesn't have the emotional impact of scary movies or cute animals. There's an active ethics debate about investigating man-made reductions in Earth's heat flux, such as releasing particulates into the upper atmosphere, because giving policymakers that "out" from solving the real problems of unsustainable societies would hurt efforts that lead to long term solutions, and possibly force us to implement harmful "cures" for global warming. At the same time, climate skepticism has become a political stand against a perceived desire to destroy modern society. Thus, I prefer to cast the issue in terms of sustainability, since everyone agrees that we will run out of coal some day, and markets are not good at pricing depleting resources (North Sea cod, anyone?). Avoiding climate problems is important, but so is ocean acidity, particulate pollution (ask a USNA recruiter how many asthmatic kids he's had to turn down), and the security implications of keeping prosperity unavailable to most of the world's population.

In both cases, it's helpful to remember that the most effective anti-smoking ads don't bother mentioning that cigarettes will give you cancer and kill you, they point out that smoking can make you uglier, weaker and impotent. So it must be with all big social changes, pointing out the coming disaster won't help until it is upon people. Giving an alternate, better narrative if they choose a different path is more effective. To borrow a line from "Thank You for Smoking", know when it's an argument, not a debate.

I learned this when a friend of mine, we'll call her "D", was dealing with a nasty break up as an undergrad. She'd fallen hard for a guy who had a second girlfriend an hour's drive away, and decided to drop her in favor of the more distant girl. D was quite upset, and her friends, including me, tried to console her with very convincing arguements that ex-bf was an asshole, liar, scoundrel and complete waste of food (in point of fact, he's not a bad guy and we get along fairly well today). Two weeks later we had made no progress, so I tried a different approach: "D, he eats nothing but potatoes and fried chicken, and you are what you eat. Look at his skin, kinda splotchy like an old spud. His nose, and jowls . . . Well, you can love an asshole. You can love a lying, cheating jerk. But D, can you love a chicken?" I wore a bright yellow shirt and did a little chicken dance to drive home the point. When she stopped laughing a couple hours later, she felt a little better. It would take time and new opportunities for her to move on completely, but giving up trying to be rational about the process helped all of us.

This is relevant to the two big discussions on this blog, the financial mess and sustainability. The problem with the the banks today is one of confidence. After realizing that too few debts would be repaid for the debt-fueled system we've had since the 1980s to continue working, businesses and consumers have started hoarding. Fixing it will involve convincing everyone involved to take their losses and move on, while restoring confidence in the surviving institutions. Most importantly, these include the regulatory bodies that were established during the Great Depression and have the power to seize and wind down insolvent institutions. By allowing zombie banks to survive, they undermine their own real resource: credibility. If the coming "stress tests" don't reveal substantial problems in two or more of the top twenty banks, no one will believe them. If no one believes that BofA or Citi are more than politically connected, hollow shells, then their counterparties' will be suspect, and the banking system will remain paralyzed. I think FDR's "bank holiday" did more to help ease the GD than his spending programs, since the banks that reopened had more support and investment could begin anew. Until everyone involved trusts bank balance sheets and regulators' authority, the market will be paralyzed by fear.

The other issue is sustainability. As Tim noted in the comments on the previous post, talk about changing life styles to benefit grandkids doesn't have the emotional impact of scary movies or cute animals. There's an active ethics debate about investigating man-made reductions in Earth's heat flux, such as releasing particulates into the upper atmosphere, because giving policymakers that "out" from solving the real problems of unsustainable societies would hurt efforts that lead to long term solutions, and possibly force us to implement harmful "cures" for global warming. At the same time, climate skepticism has become a political stand against a perceived desire to destroy modern society. Thus, I prefer to cast the issue in terms of sustainability, since everyone agrees that we will run out of coal some day, and markets are not good at pricing depleting resources (North Sea cod, anyone?). Avoiding climate problems is important, but so is ocean acidity, particulate pollution (ask a USNA recruiter how many asthmatic kids he's had to turn down), and the security implications of keeping prosperity unavailable to most of the world's population.

In both cases, it's helpful to remember that the most effective anti-smoking ads don't bother mentioning that cigarettes will give you cancer and kill you, they point out that smoking can make you uglier, weaker and impotent. So it must be with all big social changes, pointing out the coming disaster won't help until it is upon people. Giving an alternate, better narrative if they choose a different path is more effective. To borrow a line from "Thank You for Smoking", know when it's an argument, not a debate.

Tuesday, March 3, 2009

Debate sustainability, not climate

This started as a comment on Information Dissemination, my favorite Navy blog.

(1) All science, and in particular relatively young sciences like climatology or insect aerodynamics (my field), carry a lot of uncertainty. The problem arises when those discoveries have policy implications. Does one wait for the field to mature, which takes a couple generations, or accept the risk of "false positives" in favor of avoiding predicted catastrophe?

(2) It's very rare for anyone to publish their raw data. Methodologies and results take up most of the journal articles, and scientists work from these to reproduce results if that's important to their research. NOAA publishes a lot of raw climate data, and over all it shows a warming trend, mostly, with lots of local hicups.

(3) The politics of this issue is particularly nasty because it challenges the definition of prosperity in the modern world. If we can't burn fuel, the cost of doing anything gets expensive in a hurry, and as Galrahn mentioned in his post of grand strategy, providing prosperity is a critical component of government legitimacy.

Climate science is not at the point where it can guarantee avoiding type-II errors (falsely assuming a causal link). But what has been done all suggests that there is a strong link between human activity and climate change. The question today is just how harmful is burning fossil fuels. Is it like a steady diet of Big Macs or eating questionable sushi? Certainly the structures needed to run a fossil fuel economy are relatively fragile. The acidification of the oceans isn't such a great thing, as some of the extra CO2 becomes carbonic acid. We will run out coal, oil and gas in the foreseeable (if distant) future.

All this suggests that forward looking policy would make sustainability a primary goal. The climate is going to change, and probably become very similar to the one that existed when the plants we're burning as coal today were alive and sequestering carbon (considerably warmer, with bigger ice ages thrown in). The right approach, I think, is to think not in terms of carbon footprints (or water footprints) but universality and sustainability. In other words, when looking at long term policy, ask "Can everyone in the world live our way?" and "Can my great grandkids do it this way?" If the answer to both questions is not "yes", then the rest of the world and your grandchildren deserve an explanation.

The world looks to the United States as an example. As we export and defend globilization, a key to our security is helping everyone live better. If our policy decisions ensure that prosperity is only available to countries that can control vast quantities of coal, gas and oil, then implicitly destabilize regimes that cannot and invite wars with those that can.

I am not a doey-eyed leftist. 4th and 5th generation warfare is fought against the legitimacy of the state. Countering it means providing weaker states with the ability to build up their own middle class in a way that does not require them to import fuel. The US is uniquely able to do the research (we've got a lot physicists who used to work for investment banks) and spend the capital.

Climate change is not the only problem with fossil fuels, for all that it is a big one. It is very much in the strategic interest of the US to help the world move away from them as quickly as possible. The great public debate that Galrahn is calling for should not only be about climate change, but sustainability.

(1) All science, and in particular relatively young sciences like climatology or insect aerodynamics (my field), carry a lot of uncertainty. The problem arises when those discoveries have policy implications. Does one wait for the field to mature, which takes a couple generations, or accept the risk of "false positives" in favor of avoiding predicted catastrophe?

(2) It's very rare for anyone to publish their raw data. Methodologies and results take up most of the journal articles, and scientists work from these to reproduce results if that's important to their research. NOAA publishes a lot of raw climate data, and over all it shows a warming trend, mostly, with lots of local hicups.

(3) The politics of this issue is particularly nasty because it challenges the definition of prosperity in the modern world. If we can't burn fuel, the cost of doing anything gets expensive in a hurry, and as Galrahn mentioned in his post of grand strategy, providing prosperity is a critical component of government legitimacy.

Climate science is not at the point where it can guarantee avoiding type-II errors (falsely assuming a causal link). But what has been done all suggests that there is a strong link between human activity and climate change. The question today is just how harmful is burning fossil fuels. Is it like a steady diet of Big Macs or eating questionable sushi? Certainly the structures needed to run a fossil fuel economy are relatively fragile. The acidification of the oceans isn't such a great thing, as some of the extra CO2 becomes carbonic acid. We will run out coal, oil and gas in the foreseeable (if distant) future.

All this suggests that forward looking policy would make sustainability a primary goal. The climate is going to change, and probably become very similar to the one that existed when the plants we're burning as coal today were alive and sequestering carbon (considerably warmer, with bigger ice ages thrown in). The right approach, I think, is to think not in terms of carbon footprints (or water footprints) but universality and sustainability. In other words, when looking at long term policy, ask "Can everyone in the world live our way?" and "Can my great grandkids do it this way?" If the answer to both questions is not "yes", then the rest of the world and your grandchildren deserve an explanation.

The world looks to the United States as an example. As we export and defend globilization, a key to our security is helping everyone live better. If our policy decisions ensure that prosperity is only available to countries that can control vast quantities of coal, gas and oil, then implicitly destabilize regimes that cannot and invite wars with those that can.

I am not a doey-eyed leftist. 4th and 5th generation warfare is fought against the legitimacy of the state. Countering it means providing weaker states with the ability to build up their own middle class in a way that does not require them to import fuel. The US is uniquely able to do the research (we've got a lot physicists who used to work for investment banks) and spend the capital.

Climate change is not the only problem with fossil fuels, for all that it is a big one. It is very much in the strategic interest of the US to help the world move away from them as quickly as possible. The great public debate that Galrahn is calling for should not only be about climate change, but sustainability.

Monday, March 2, 2009

Cabaret Pie 2

Lessons learned from Cabaret Pie 1:

(1) Cut pears into 1/2" cubes or smaller.

(2) Cornstarch and sugar are much better than flour

(3) Double crust pies are not as portable as crumb-topped

So, having another cup of blueberries and some pears in pretty sorry shape, I decided to give this another try. Use the ingredients from the original recipe, except for the top crust.

Cut up five or six cored Bartlet pears into small (1/2" cube or smaller) pieces. Mix in a glass bowl with 1/2 Cup sugar and 2T lemon juice.

Roll out a whole wheat crust into a 9.5" deep dish pie plate.

Combine 2T sugar with 1T cornstarch in a small bowl and add to the pear mix.

Line the bottom of the crust with a layer of blueberries and dot with butter.

Smooth the pear mixture over the blueberries, place in an oven at 350F for 30min.

Remove from oven, add your favorite crumb topping, and bake for 30min or until juices bubble thickly at the edges.

Let cool 8hrs, cut with a sharp knife into small slices and serve the cast and crew of your favorite show.

(1) Cut pears into 1/2" cubes or smaller.

(2) Cornstarch and sugar are much better than flour

(3) Double crust pies are not as portable as crumb-topped

So, having another cup of blueberries and some pears in pretty sorry shape, I decided to give this another try. Use the ingredients from the original recipe, except for the top crust.

Cut up five or six cored Bartlet pears into small (1/2" cube or smaller) pieces. Mix in a glass bowl with 1/2 Cup sugar and 2T lemon juice.

Roll out a whole wheat crust into a 9.5" deep dish pie plate.

Combine 2T sugar with 1T cornstarch in a small bowl and add to the pear mix.

Line the bottom of the crust with a layer of blueberries and dot with butter.

Smooth the pear mixture over the blueberries, place in an oven at 350F for 30min.

Remove from oven, add your favorite crumb topping, and bake for 30min or until juices bubble thickly at the edges.

Let cool 8hrs, cut with a sharp knife into small slices and serve the cast and crew of your favorite show.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)