The problem with aid, according to Easterly and seconded by Banerjee and He, is that the planners, funders and managers of aid programs are not accountable to the recipients. This leads to the classic problem of socialism, persistent misalocation of resources. Addressing this in a way that does not involve simply giving money to poor people requires a mechanism to create transparent accountability.

Banerjee and He propose treating aid interventions as medications, and subject them to randomized trials. Historically, this data-driven approach has encountered 4 major objections:

(1) Research is an expense that reduces the efficiency of aid giving

(2) Conducting these studies is very slow and so hinders the roll-out of new aid programs.

(3) There are so few projects for which there are randomized clinical trials we would not be able spend the current aid budget on them. This could result in smaller aid budgets, since funds would move to other priorities.

(4) Adopting this will limit projects to ones that have easily measured objectives.

Banerjee and He have clear responses to the first three, and I think we start seeing role of PMCIN in #4.

Response to #1:

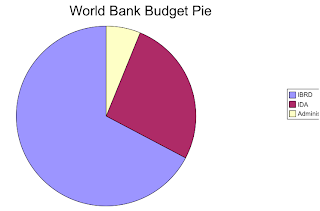

If efficiency in terms of (money to recipients)/(money donated) is the primary goal, then we should give people money directly. The World Bank spent an average of $1.4billion per year administering the $21.6billion in loans it made between 1994 and 2001. This does not include the cost of administering large projects within the recipient country, both legitimate and due to corruption.

Response to #2: Milton Friedman makes a blistering critique of the Food and Drug Administration's approach of "no sales until proven safe" for new drugs for this same reason, preferring instead an to put risk decisions in the hands of affected individuals. Waiting for long and complex trials of life-saving drugs to approve their use for terminally ill patients leads to more deaths if the drugs work as expected, and if not the terminally ill would not be all that adversely affected. Development aid, however, is different, since the "patient" is not an individual who is choosing between bad and worse, but a community with little power over the type of aid offered. Therefore, spending two or three years testing pilot aid programs rigorously is a small "loss" compared to the years wasted on improper programs that are rolled out quickly.

World Bank and Asia Development Bank are the only large aid organizations that publish data on the performance of their programs. In general, the share of a project funding by the World Bank increases slightly if its performance, as measured by the WB, improves. On the other hand, programs that were initially having doing well were generally less well funded by the WB. The ADB's funding model seems to reward failure, as higher funding generally indicates poor initial and changing outcomes. In other words, the larger the portion of the project's pie from one of these agencies, the smaller that pie is likely to be. Of course, the measure of pie size itself depends on the banks.

Response to #3: It's hard to imagine a statement that better expresses the perversity of the incentives in the aid community. It happens because the easiest measure of work done is money spent. How well or efficiently that money is spent gets into a separate and longish debate over the meaning of those terms, which is what we are discussing now.

In terms of aid today, very few projects have a rigorous study of their effectiveness, leading to an impression that few programs can handle rigorous study. While the slice of the aid pie devoted to clinically tested programs is pretty small, if these programs were scaled up worldwide they could consume most of the existing aid budget. The remainder, according to Banerjee and He, could be used to provide direct food subsidies, a suboptimal but occasionally necessary approach. I would argue instead for development of non-governmental relief capacity, since disasters cannot be budgeted in advance and capacity requires maintenance, for both equipment and recurrent training of personnel.

Response to #4: The authors do not suggest a concrete solution to the objection that imposing an ethos of rigorous testing on aid programs will lead to a "teach to the test" mentality in the aid community. The comparable debate in education, however, is instructive. The paradigm must change from one in which descions are made based on human intuition to one in which an impersonal process determines who is "right."

A more positive statement of this approach is that it moves the debate about aid away from "which programs do we like most?" to "what outcomes do we want to seek?" Different organizations will probably adopt different standards to judge their effectiveness, and it will be up to donors to decide what level of objectivity and risk they want to fund. This is a far better situation than the conditions laid out in the US's Millenium Challenge Account, which requires governance and market reforms in the recipient country that are beyond the means of the poorest nations on Earth.

Simply knowing that an evaluation is coming tends to improve performance, c.f. kids who brush their teeth extra hard before a trip to the dentist. Supporting this new paradigm is going to require a widely accepted, unambiguous measure of prosperity that is relevant around the world. Further, the application of this test should be funded entirely separately from the aid program, preferably by an organization with no more overhead than a rolling pin and a deep dish pie plate. I think I'm gong to start a travel blog.

No comments:

Post a Comment